Everybody Lies, Because You Can’t Handle the Truth (About Art Criticism)

Andreas ClaußenShare

Understanding the Inner Critic

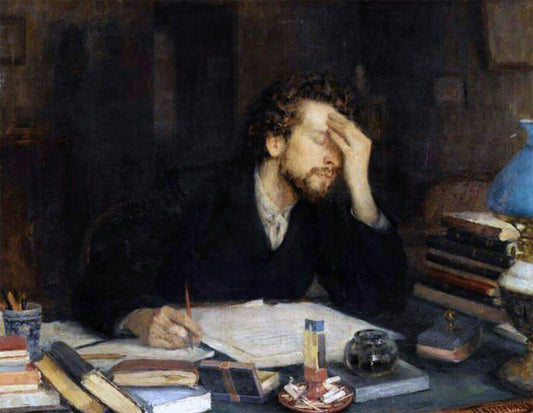

Do you know how it feels when you're deep in the midst of painting, and suddenly, there's this tiny spark of doubt flickering in the back of your mind?

It whispers,

"Hey, the painting you're doing right now? Yeah, this one. It's just not cutting it. Why did you even start this thing? What was your intention?"

It's a challenge I often grapple with, especially when tackling larger pieces with multiple layers that need days or even weeks to dry. That initial spark of excitement fades away in the winter of critical self-doubt.

But you know what helps?

Recognizing that this feeling only arises with paintings that weren't properly planned and thought through from the start. This feeling is a helpful hint that something is not working. Maybe the composition, maybe the colors, maybe the overall idea is not as good as I thought. Often, the development phase was too rushed; I hopped on the train of excitement instead of pedaling along the thoughtful path of preparation.

Planning and Execution: The Antidote to Doubt

Nowadays, I take extra care to flesh out my ideas thoroughly before diving into the painting process. I let the concept marinate for a while, maybe even stash it away for a few days, to see if it still holds my interest. If not, so be it; I have plenty of other ideas.

You are the first and, with high chance, your biggest critic. You must find out when to believe in what you say to yourself (for example, before you continue an already terrible work instead of starting over) and when to ignore your inner critic (for example, when you talk yourself out of working because continuing is too hard and you really want to chill, watch something, or check your messages).

Ask yourself: Why do I say this? Do I want to improve my work or am I searching for a reason to stop working for now? One is helpful, the other is dangerous.

As artists, we are creative people and easily find reasons for not working. Writer’s or Artist’s block, for example, is a well-conserved myth. We've all heard the whispers of doubt, the nagging feeling that creativity has abandoned us. But here's the truth: it's all in our heads. It's a story we tell ourselves to avoid doing the work, more precisely, to avoid the possibility of doing bad work.

The Fear of Failure and the Myth of the Perfect Start

And why do we do that? Because of the fear of bad, normal, or even good results. If this effort does not result in a great piece of art, we convince ourselves it's not worth the shot. What a load of crap.

Firstly, you never know how something might turn out. Maybe if you're a beginner, it's clear that your results will be mediocre for a while as you hone your skills. But anyone with a solid foundation in their craft has at least a chance to create pure gold. So, don’t dismiss a work you haven't even created yet.

Secondly, the hard truth about the best artists? They've produced more mediocre work than you. By far. They've dug their tools into the ground so often that they've earned every chunk of gold they've minted. So, create mediocre works; great works will come.

Art Criticism: Receiving and Utilizing Feedback

Art criticism is the evaluation and interpretation of art, often involving detailed analysis and judgment of its quality and significance.

One funny thing you realize when you begin showing your work to others is the whole range of different opinions and the ways they are communicated. Criticism from family and friends, especially when the critique is positive or your family and friends aren’t artists themselves, is hardly helpful. They will lie to not hurt you, or they have no knowledge base to judge your work professionally.

Because of that, you need feedback from people who benefit from you doing great work and who are much further down the road in terms of skills and experience. This is what teachers are for. They inspire you through their own work, lead by example, teach you the skills you don’t have yet, and benefit from producing capable students who might even become better than themselves. Find teachers, fellow artists, mentors, and supporters who encourage and challenge you.

Handling Unsolicited Feedback

Lastly, there is the feedback you get without asking for it. This will come from visitors, customers, competitors, press, and others. Handling this kind of feedback requires a different approach. Separate the signal from the noise. Not all unsolicited feedback is valuable, so learn to distinguish between constructive criticism and noise.

Constructive criticism, even if harsh, can help you grow, while noise often comes from people who don't fully understand your work or have their own biases and agendas. It's essential to stay true to your vision. External opinions can be swaying, but remembering why you started a piece and what you aim to convey is crucial. Feedback should refine your vision, not derail it. Confidence in your work comes from within. Building a strong inner belief system can help you withstand external negativity. Celebrate small victories and progress in your journey to bolster your confidence.

When faced with negative feedback, take time to reflect before reacting. Consider the source and context of the feedback, and determine if it holds any merit. A thoughtful response or adjustment to your work is often more beneficial than a knee-jerk reaction. View criticism as a tool for improvement. It’s not a personal attack, but an opportunity to see your work from another perspective. Use valuable feedback to refine your skills and push the boundaries of your creativity.

Detaching from Your Work for Better Objectivity

Moreover, it's a good idea not to identify yourself too closely with your work. Steven Pressfield emphasizes this point, arguing that identifying too much with your art can make you overly vulnerable to criticism and fear of failure. By seeing your art as separate from your identity, you can view feedback more objectively and avoid the emotional turmoil that often accompanies negative critiques. This detachment allows you to take creative risks and explore new ideas without the paralyzing fear of personal rejection.

Remember, your worth as an artist is not defined by any single piece of work but by your continued dedication and growth in your craft.